Especially during the current pandemic it would be very hard to live without some of our favourite products/services, that mostly appeared since the beginning of the millenium: Facebook, Twitter, Amazon, Spotify, HelloFresh - just to name a few.

Although these and other favourite products of generations x, y & z are very different in nature, they often have 1 thing in common: venture capital. Some would even argue that without venture capital financing some of these products wouldn’t even exist today. Nevertheless it is almost guaranteed that those products would be different or their wider adoption level would be less without venture capital.

But what exactly is venture capital?

While Venture Capital (VC) is among the most preferred and frequently used financing options for startups, many founders are not very familiar with the definitions of various venture capital contractual terms – sometimes even after an investment has already taken place. For the sake of fairness, these contractual terms are quite complex and thus contracts are quite long.

Since VC contracts are private agreements, individual arrangements and wordings are up on negotiation. However, there is a basic set of frequently used mechanisms that can be considered somewhat “standard terms.” Still, in contracts – as well as in the dozens of books, presentations and many blogs and comments on those – the language used is formal and based on legal standards.

Therefore, they are close to what founders will officially sign, but are still difficult to understand for beginners.

Disclaimer: If you want legally binding and comprehensive solutions for VC contracts, you shouldn’t read any further.

You can find those at German Standards Setting Institute (in German legal language) or if you talk to professional lawyers such as our partners CMS HS or KPMG or if you read comprehensive books like “Dealterms.VC” by our friend and mentor Nikolas Samios (PropTech1 Ventures) or “venture deals” by Brad Feld.

But if you need a quick overview to immediately understand typical terms (under German law and market standards), feel free to find it here.

Without further ado, here's 10 venture capital definitions you can learn today

/Venture_Capital_unsplash.jpg?width=1000&name=Venture_Capital_unsplash.jpg) In order to set up a proper contract, you need to know the basic terms

In order to set up a proper contract, you need to know the basic terms

1. Liquidation Preference

In case of a liquidation (e.g. exit or insolvency), the last investors who invested get back their invested sum first (“preferred stock”), the remains (“common stock”) are paid back to all investors according to the shares they own (“pro-rata”) – this is the case of a participating liquidation preference.

If there have been several financing rounds with liquidation preferences, you go step by step from the last round to the first round (“stacked preferences” or “waterfall”).

Sometimes this means that all investors get their money back, but it is nothing left for the founders. Thus, this mechanism is a downside protection for investors, who want at least their money before founders earn something.

2. Vesting

In case you leave your startup voluntarily within a defined (vesting) period – often up to 48 months -, you will have to give back shares to the company. These shares can be distributed among other shareholders (e.g. new co-founders). In this way, founders and early investors protect themselves against losing co-founders very early.

Usually, if founders leave within the first 12 months, they lose all of their shares (cliff). For each additional month they can retain 1/48 of their shares in case they leave. Often, vesting clauses are different for good leavers (when both parties agree that a founder shall leave the management team) and bad leavers (a founder gets a dismissal for cause).

Vesting rules should also be applied to ESOP programs (employee vesting), to avoid blocked (virtual) shares by employees who left the company early.

3. ESOP

Employee Stock Ownership Plans are an instrument to incentivize key employees by sharing exit proceeds/returns with them. To avoid management complexities, this is frequently done through virtual stocks without voting rights.

In practice, this means that founders (typically other shareholders are not included) sign a contract to share usually 5 or 10 percent of their proceeds with a holding that splits these amongst participating employees.

/signing-contract_unsplash.jpg?width=1000&name=signing-contract_unsplash.jpg) Even if you feel like things are going well, consider including vesting rules for you, your co-founders and your team.

Even if you feel like things are going well, consider including vesting rules for you, your co-founders and your team.

4. Pre-Emptive rights

Existing investors have the right to participate pro-rata in future capital increases of a startup.

5. Tag Along Right

If one or more shareholder sell their shares to an external party, all other shareholders have the right to sell their shares at the same price and conditions. If the buyer does not accept to buy all shares, the deal is stopped.

6. Drag Along

If the majority of shareholders intends to sell their shares to a third party, all shareholders can be forced to sell their shares at the same price and conditions.

7. Right of First Refusal

If one shareholders wants to sell shares, all other shareholders are allowed to buy these shares at the price and conditions the selling shareholders officially announces (in a document called “transfer notice”).

8. Anti-Dilution

When things don’t run as expected (unfortunately, quite often the case in startups) it may happen, that a future investment round takes place on a lower valuation than the previous investment round (“downround”).

In other words: investors paid too much in the earlier round. Anti dilution clauses cause investors to get additional shares for their overprized first round in case of a downround, meaning a belated valuation decrease of the first found.

Make sure to get into the details of your contracts when considering Venture Capital as an financing option.

9. Pay-to-play

If an investor is not particating in future rounds (at least pro-rata), he can lose special rights (e.g. Right of first refusal, liquidation preferences etc.)

10. Advisory Boards

Unlike stock corporations, smaller startups under German law are not forced to build a supervisory board (and by law, supervisory board members are liable and regulated). Therefore, investors both want to execute their rights of information and voting as well as they want to support startups with their expertise.

Frequently, they require “voluntary” advisory boards staffed by investor and sometimes founder representatives that gain certain rights.

Read our blog article on advisory boards, if you want to learn more about it.

4 Important terms one must comprehend to understand a VC system

So while the above terms are some blanket terms that everyone should be familiar with when entering the VC world, there are also some terms that are crucial to understanding how the system itself actually functions.

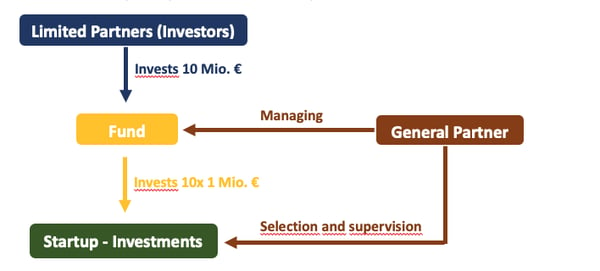

1. Limited Partners (Investors)

Limited Partners (LPs) are external investors such as large corporate companies, family offices, or wealthy individuals who want to invest their money with the willingness to take on a higher risk than normal retail investors. On average, LPs expect a return of 15-20% p.a. over the fund duration of 7-10 years.

2. Fund

The Fund is the final bucket where all the money is collected. The process of searching for investors and negotiating about the terms of investments in the fund are called fundraising. Investments that are conducted are taken from the fund.

The size of the fund is a good indicator for the size and experience of the VC (the longer the VC is in the market, the higher the trust – if they performed well – and the more likely investors are to re-invest even larger sums). A normal fund has a lifetime of about ten years, with an investment period of five years and a cash-out /further investment phase of the missing five years.

The longer the VC is in the market, the higher the trust – if they performed well – and the more likely investors are to re-invest even larger sums

3. General Partners

General partners are employees of the VC and are comparable with the CEO of traditional companies. Normally, they also are the founders of the fund or joined before the next fundraising process has started.

The main responsibility of GPs is the investment decision (final decision maker). In order to give LPs a better feeling and to ensure general partners will invest foreign money only in high-potential targets, GPs are also financially involved in the fund by a certain percentage.

/math.gif?width=538&name=math.gif)

Besides, the management is additionally incentivized by receiving a management fee of the fund (comparable to a salary) and receive a provision (around 10%) at the end of the fund duration if they surpass the hurdle rate (minimum rate of return on a project required by investors, typically around 15-20% after five to seven years).

4. Startup InvesTments

Finally, after an average time of three to four months and the agreement on final terms, the actual venture starts, and the investment is conducted. In a typical startup portfolio of a VC there are specific numbers about how much money (multiples1) each investment returns.

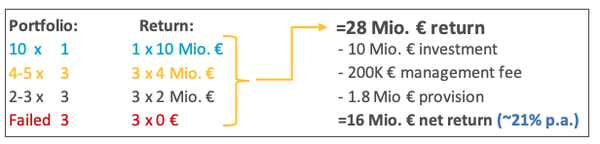

For an easy explanation, let us assume that there have been ten investments in total. History has shown that around 30% of the VC backed companies fail. So, the return from the VC´s perspective will be 0€.

Three other portfolio companies have a multiple of two to three x followed by three other investments that return four to five x. Consolidating all the returns, the total return would hardly cover the money invested plus a 15-20% additional return for the LPs.

VC’s expect the tenth investment to return ten x or more. This one investment alone is expected to return the whole fund, that’s why it is called the fund returner.

Let’s have an easy example (Caution, some easy math included):

After fundraising, the fund reached an amount of ten Mio. €. General partners seek good investment opportunities and invest into ten startups, one million € each.

Unfortunately, three investments go bankrupt after a few ears, three startups have the expected return of two x and four x respectively.

Then the VC showed some good feelings about the development of the tenth startup which becomes the fund returner with a return of ten Mio. €. See the calculation in the following box:

The total ROI cumulates to 28 Mio. €. Deduct the fund size, a management fee of two percent, ten percent provision and the LPs end up with a net revenue of 16 Mio €, which is some 21% ROI per year. The VC performed quite good and surpassed the expectations of the investors (LPs).

Play with the numbers and see how the net revenue changes if there is no fund returner or half of the portfolio fails.

Conclusion

VC ain't easy! We've done our best here to break down this highly complex topic into simple terms using practical examples, but as you can see, even when trying to be simple it still becomes slightly complex.

If you want to learn more about VC deal terms, your negotiation power discussing with investors and other financing topics, apply to our SpinLab program here.

If you've got any questions or need clarification on anything, let us know in the comments!

/Contract_unsplash.jpg?width=1000&name=Contract_unsplash.jpg)

/RootCamp_Logo-Ecosystem.png?width=200&name=RootCamp_Logo-Ecosystem.png)

/Bitroad_Logo-Ecosystem.png?width=200&name=Bitroad_Logo-Ecosystem.png)

/White%20Versions/stadt_leipzig_white.png?width=130&name=stadt_leipzig_white.png)

/lfca_white.png?width=119&name=lfca_white.png)

/White%20Versions/sachsen_signet_white.png?width=65&height=79&name=sachsen_signet_white.png)